Two Ways to Translate:

Domestication and Foreignization

A Methodological Approach

It can be that the very act of translating is most directly concerned with finding correspondences in the target language, so that the translation conveys in the TL what is originally conveyed in the original language. That is to say, translation is primarily about the rendering of actual linguistic signs from one system into another. There can be countless accounts of why vastly different from one another, but the general options of how can be relatively narrowed down.

Surely, it is difficult to argue in favor of one translation methodology over another unless the real purpose of translating a given work is specified. Because the two linguistic systems are made up of different rules and features, there seem to be two main directions to which the translator can proceed. She can either try to be faithful to the formal structure of the original text, or she can liberally modify her translation. These two directions form a commonly used dichotomy of translation methodology today: ‘domestication’ versus ‘foreignization,’ which was first coined by Friedrich Schleiermacher in the 19th Century and then revitalized in the contemporary age by Lawrence Venuti.

According to Schleiermacher in "On the Different Methods

of Translation" (1813), domestication "leaves the

reader in peace as much as possible and moves the writer

toward him," and foreignization "leaves the author in peace

as much as possible and moves the reader towards him".

To foreignize is to practice strict fidelity to the syntax of the

original language, at the risk of confusing the readers of the

target language. By contrast, to domesticate is to modify the

structure of the original and thereby prevent such confusion,

as though the text were originally written in the target

language. In sum, domestication is liberal paraphrasing

that seeks to make the translation approachable and familiar for the target-language audience, and foreignization is literal translation that seeks to be as close to the original syntax as possible.

Although Schleiermacher considers foreignization better suited to conveying the original author’s intent, he introduces this dichotomy as a helpful reference point from which the translator can go about what Jakobson calls the "creative transposition" and produce a well-balanced translation. In other words, he provides a framework for the main directions that translator can take, but does not go so far as to prescribe which direction she ought to take.

To note before we look at a few arguments that do prescribe, the prevailing opinion seems to be that foreignization—that is, syntactic fidelity or literalness—is better in terms of letting the reader experience the effects of the original's formal configuration. I, too, believe that formal techniques and "autonomous significations" of grammatical categories are important elements that contribute to the literary value of the text, and that trying to be as faithful as possible to the original structure will give the reader a better chance to at least get a glimpse of the effects of the original.

(But, as we will see in the next chapter, both domestication and foreignization are little more than general theoretical frameworks and are not fully realizable. Any close translation will end up incorporating a little bit of both.)

For Venuti, who has been spearheading the development of translation theory as a separate consideration, this dichotomy serves a decidedly political function. In his view, literature itself, as long as it involves real people whose lives are affected by the international market, is inseparable from the political and economic conditions in which it is produced.

In his book The Translator’s Invisibility (1995), Venuti argues that domestication has been the unspoken norm in Anglo-American culture and led to a form of cultural imperialism. A translation in English is “judged acceptable by most publishers, reviewers, and readers when it reads fluently, when the absence of any linguistic or stylistic peculiarities makes it seem transparent, giving the appearance that it reflects the foreign writer’s personality or intention or the essential meaning of the foreign text”.

Because domestication prioritizes convenience for the

target-language reader by creating an "illusion of transparency",

it results in "less an exchange of information than an

appropriation of a foreign text for domestic purposes". In the

Anglo-American context, a domesticated text not only makes the

translator "invisible" by appearing as though it were originally

written in English, but it also reinforces underlying political

hierarchy between the speaker groups of the languages involved.

According to this view, when an English-language translator liberally translates a Korean text to give it a more familiar appeal for the English-speaking readers, this would be an instance of "masquerading as true semantic equivalence" when it is in fact "partial to English-language values, reducing if not simply excluding the very difference that translation is called on to convey".

Foreignization, on the other hand, would serve the goal of

countering the privileged status of English that has political

implications. Venuti says, although foreignized translations

are "equally partial in their interpretation of the foreign text",

they still "tend to flaunt their partiality instead of concealing

it" as domesticated ones would. With this reasoning, Venuti

explicitly states why translators should practice literal

translation: "to make the translator more visible so as to

resist and change the conditions under which translation is

theorized and practiced today, especially in English-speaking

countries".

Nothing But the Text

If you found Venuti's argument quite contentious, you might think that he is voicing his opinions strongly because his theory is explicitly tied to his views on the current political inequality and market structure. If he did not have such a decidedly political agenda, we might speculate, he would have been more open to the method of domestication.

As we will now see, the contentiousness of one's argument can also be nonetheless motivated by 'aesthetic' concerns. Of course, there is reason to argue that what we call aesthetics in literature is not at all separate from the political and economic contexts in which the texts are produced and distributed; yet again, whether or not to treat beauty and reality separately is a matter of one's philosophy at large.

In his essay (1955) accompanying his English translation of

Alexander Pushkin's 'novel in verse' Evgeny Onegin,

Vladimir Nabokov makes a no less fuming case for

foreignization. He argues strongly for a faithful rendering of

the original’s syntax than does Venuti less for achieving

anti-imperialist justice than for making the best possible

attempt at preserving the "autonomous significations" of the

original text.

He finds words like 'fluency' and 'transparency' despicable:

"I constantly find in reviews of verse translations the

following kind of thing that sends me into spasms of helpless fury: 'Mr. (or Miss) So-and-so’s translation reads smoothly' ". Were he to speak in terms of Schleiermacher’s dichotomy, Nabokov would not even consider domestication a viable form of translation: "The term 'literal translation' is tautological since anything but that is not truly a translation but an imitation, an adaptation or a parody". So it is not even translation if it does not retain the linguistic structures of the original text. He equates "literalism" to " 'absolute accuracy' " and argues that the sole duty of the literary translator is "to reproduce with absolute exactitude the whole text, and nothing but the text".

Swiftly, Nabokov acknowledges that complete literalism is impossible, since he himself was unable to translate the “autonomous significations” of Russian prosody in Evgeny Onegin into English, despite his firm grasp of the two languages. Russian-speaking readers often stress that Pushkin made brilliant use of grammatical categories to create poetic effects,

such as case markers (which I briefly mentioned

in the introduction), which becomes

problematic for the English translator, because

English marks case very rarely.

Because Pushkin's choices of case markers must

disappear in English, it can be said that this

aspect of his poetry is untranslatable. According to a book on Pushkin (1926) by D.S. Mirsky, Ivan Turgenev, another Russian novelist, made his own French translations of Pushkin's poems and presented them to the French novelist Gustave Flaubert. After reading the translations, Flaubert is reported to have said to Turgenev: "Il est plat, votre poète" ("He is flat, your poet").

Although Nabokov argues that the best alternative is to stay as faithful to the original syntax as possible, he admits that the unique prosody and the rich case morphology of Russian cannot be directly translated into English. Instead, he proposes that the translator should explain the untranslatable elements of the text with many supplementary footnotes: “I want translations with copious footnotes, footnotes reaching up like skyscrapers to the top of this or that page so as to leave only the gleam of one textual line between commentary and eternity”.

Faith in Poetic Truth

Not all prominent writers showed such a strong preference for foreignization. Jorge Luis Borges went against the current to voice support for the translator's liberty to paraphrase and find alternative equivalents in the target language.

In his short essay "Two Ways to Translate" (1923), Borges names “literality” and “paraphrase” as the two methodological options and explains: “The former corresponds to the Romantic mentality, the second to the classical”. Although he does not employ the very words foreignization and domestication, Borges’s own dichotomy is defined similarly. For the “classicists,” to paraphrase is to search for the absolute and despise the particular in order to attain a certain “poetic truth” that is not bound to an individual but universal. The literal, “Romantic” translation, by contrast, is rooted in “the reverence for the I, for the irreplaceable human that is any I”.

For the Romantic translator, the foreignizer immersed in

the foreign, “everything becomes poetic in the distance,”

and she becomes “a charlatan” who must “roughen the

rough edges” and “sweeten the sweetness” in order to

“maintain the strangeness of what he’s translating”.

Therefore, Borges suggests that the very idea that strict

fidelity can be fully exercised with the foreignizing attitude

might be an illusion.

Instead, he prefers the “classicist” ideology, which argues that good paraphrase can expose “poetic truths” that are not restricted to a particular language and culture. In Borges’s ideal view, the literature of every language "possesses a repertory of these truths, and the translator knows how to take advantage of it and to pour the original not only into the words but into the syntax and usual metaphors of his language”.

Even though Borges acknowledges that many other writers object to the idea of paraphrasing liberally at the translator’s own discretion, and that “this objection is difficult to oppose,” he still maintains: “I am of the opinion that even poetry is translatable”.

There is more than one way to interpret what Borges means by all this. From a pragmatic perspective, it might be considered a wholesome message from a literary sage trying to keep readers around the world from getting too discouraged from delving into each other's poetry by the premise that they won't be able to understand it anyway. In the context of what we learned from Jakobson, we could say Borges believes that "creative transposition" is an artistic end in and of itself, not merely a pale window into the original. If that really is the case, it would indeed make more sense to paraphrase liberally (domesticate) in order to find correspondences rather than equivalents in the target language.

With that in mind, we will now compare and contrast examples of domestication and foreignization, so that each of us can decide which is better. But more importantly, I will eventually illustrate that translation is always a bit of both, always some combination of fidelity and 'unfaithful' innovation to varying degrees.

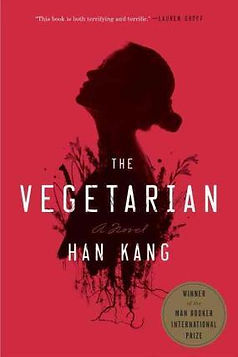

Deborah Smith's English translation (2016) of The Vegetarian (2007) by Han Kang was awarded the Man Booker International Prize, the first ever for a Korean original. A number of readers believe that Smith took too much liberty, which Smith defended as a necessary choice on behalf of the English-language reader.

Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834) was a German theologian. He gave one of the earliest methodological explanations for literay translation.

Lawrence Venuti (1953~), now a professor of English at Temple University, has pioneered the contemporary development of translation studies as an academic discipline.

Vladimir Nabokov

(1899~1977),

Author of Lolita

Ivan Turgenev

(1818~1883),

Author of

Fathers and Children

Gustave Flaubert

(1821~1880),

Author of

Madame Bovary

Jorge Luis Borges

(1899~1986),

Author of

Pierre Menard, Author of the Quijote