Limits of Formal Translation

and Its Connection to Culture

Which one are you?

It will be useful for us to go through a pros-and-cons list of examples for both domestication and foreignization, because all we've looked at so far was theory. It is important for each of us to think through real examples and decide for ourselves, because, as I will illustrate by the end of this chapter, neither answer can apply to all situations, and a compromising choice constantly needs to be made on a case-by-case basis.

In the introduction, we learned by looking at the Korean translations of Huckleberry Finn that domestication can have unintended consequences. In particular, one of the translators' decision to use the Jeolla dialect for Jim's speech could be seen as domestication, because he was making the relationship between Jim and Huck more familiar for the Korean reader by pasting a Korean sociopolitical dynamic, which he presumably considered an apt correspondence rather than a direct equivalent, right on top of it. And the resulting political implication is not trivial, because it might end up reinforcing the black-white and Jeolla-Seoul hierarchy to the Korean reader.

Domestication or liberal paraphrase can also be especially intrusive and even destructive when the original text itself uses unconventional or enigmatic language. In the case of English and Korean, many Korean translations of the so-called 'Modernist' writers suffer the bad consequences of domestication in particular, because a lot of the formal experiments they pioneered were simply brushed aside.

One quick example can be found in a Korean translation (Kim 2003) of William Faulkner's As I Lay Dying. Here is a line from the original novel:

“ Lafe. Lafe. ‘Lafe’ Lafe. Lafe. ”

This line is uttered by a character named Dewey Dell, a seventeen-year-old girl who has kept her pregnancy a secret to everyone except Lafe, the boy who got her pregnant, and Darl, one of her older brothers. She utters this line when she hears somebody lurking in a dark barn and wonders if it is Lafe waiting for her there. She iterates his names five times in a row, desperate and frightened. We will notice that only one of the Lafes has single quotation marks around it and no period after it.

What does this peculiar structure tell us? Regardless of our interpretation, we can sense that Faulkner is innovatively paying attention to the distinction between internal monologue and phonetically realized speech: just because there is a tiny pair of quotation marks surrounding it, the third Lafe is registered to the reader as different from the rest. Punctuation itself because one of the categories that has "autonomous signification".

In the translation of Kim (2003), however, we're not even given the chance to ask what this peculiar line might by signifying. Here is the translation of the same line:

" 레이프. 레이프. 마음속으로 부른다. ‘레이프.’ 실제로 소리 내어 부른다. 레이프. 레이프. "

" Lafe. Lafe. I call him in my mind. ‘Lafe.’ I actually call him out loud. Lafe. Lafe "

"I call him in my mind" and "I actually call him out loud" do not

exist in the original. They are brand new sentences liberally added

by the translator. Kim (2003) kindly went out of the way to

explicitly state to the Korean reader what he/she thinks is going

on. But what this translator does not seem to have recognized is

that being a native speaker of English would not have made things

that much different, and hence that the structure of this line was

meant to be confusingly new.

The peculiarity of this sentence is a matter of punctuation, not the

structure of the English language. There is nothing formal about it

that could not have been directly translated into Korean.

Nonetheless, the Korean reader has now lost access to a significant part of the formal value of Faulkner's experimental novel writing. In order not to annihilate the stylistic details the original that bear artistic meaning, the literary translator should carefully think about every formal aspect and ask whether it is translatable into another language.

Bad examples of domestication abound especially in translations of titles. Moby-Dick; or, The Whale was once translated into Korean as 'White Whale' (at least this title rhymes in English; but in Korean it doesn't). A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man has become 'A Portrait of the Young Artist'. Film titles are worse: Alfred Hitchcock's North by Northwest is known in Korea as 'Turn the Course to the North-ish Northwest!' Jaws was at first 'Mouth'.

But above all, I think the worst-ever Korean translation of an

English-language title was of Brazil (1985), Terry Gilliam's take

on 1984 and Don Quijote. The title for its Korean release used to

be "여인의 음모 (The Conspiracy of a Woman)". As if that alone

didn't sound like misogynistic porn, it certainly didn't help that

the word for conspiracy, 음모, pronounced eum-mo, is also the

word for pubic hair.

Benefits of Domestication

On the other hand, if the translator could always find correspondences in the target language with which to "creatively transpose", we would be able to build a very strong case for domestication. And liberal translation often does indeed lead to miraculous results that literal translation could not have produced.

For example, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne,

or Vingt mille lieues sous les mers in original French, is translated into

Korean as Hae-juh Ee Maan Lee. The Korean word lee is phonetically

very similar to its French counterpart lieues, so the translated title

smoothly resembles the original. However, lee is not the same unit of

distance as lieue. 1 lee, an old Chinese unit that refers to only about

0.393 kilometers or 0.244 miles. Since Koreans use the metric system,

a literally translated Korean title of the novel would have meant

something like 80,000 Kilometers Under the Sea. But 20,000 lees

only amount to about 7,854 km, or only about 1963.5 French lieues.

A convenient domesticated translation does not cause any of this

confusion, and the Korean reader roughly understand the more

important part, whatever the precise unit might be: the book goes way deep in the sea.

Domestication can also be a conciliatory measure that somewhat makes up for grammatical differences that could not have been foreignized (literally translated) anyway. A literal translation of the title of Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well into Korean would go along the lines of:

좋게 ‘good + Adverbial suffix’ 끝나는 ‘end + Gerundial adjectival suffix’

것은 ‘thing + Nominative suffix’ 다 ‘Adverbial all’ 좋다 ‘good + Sentence ending suffix’

We don't have to go through the meaning of each of those suffixes to see that Korean requires those suffixes very often, whereas the english original hardly ever does. Therefore, even this attempt to be strictly literal results in considerable changes in syntax. The S-V-O versus S-O-V difference in word order between English and Korean also hinders efforts to translate this title literally.

Here, that ends well as a modifier of the noun all had to move to the left of the noun, producing something like that which ends well is well all-around when literally translated back into English. Even with the strictest exercise of fidelity, a complete word-for-word translation of the phrase is, as far as I can see, impossible.

In fact, the translation commonly adopted by Koreans is:

끝이 ‘end + Nominative case’ 좋으면 ‘good + Conditional’

다 ‘Adverbial all’ 좋아 ‘good + Sentence-ending suffix’

This one is even more syntactically divergent from the original, because that ends well no longer modifies all like an adjective but undergoes transformation into a separate hypothetical condition from which the conclusion all is well can be derived: if the end is well all is well.

This version commonly embraced by Koreans is by all means domesticated. Then, what has it gained at the expense of fidelity? We are reminded of Borges's faith in the translatability of poetry by means of creative correspondences. The English phrase all’s well that ends well resounds in me most strongly for its musicality, which gets utterly lost in its literal translation into Korean. However, the domesticated version, with its colloquial suffix “-아” and a cadence similar to four-four time, succeeds at least in communicating the very existence of a certain musical property, though in an entirely different form—끝이 / 좋으면 / 다 / 좋아.

The Inevitable Compromise

We have briefly looked at some problems that can be caused by domestication and foreignization. Previously, I have mentioned Nabokov’s remark that “The term ‘literal translation’ is tautological.” Yet technically, at the same time, paraphrase is also tautological, because of the simple fact the original language and the target language are different languages. If we accept that foreignization and domestication are both are tautological, a translation would always contain a bit of both.

Take the following example, an excerpt from a poem sequence called 오감도 (Ogamdo, meaning 'Raven's Eye View') by the Korean poet 이상 (Lee Sang), first published in 1934:

13인의아해가도로로질주하오.

(길은막다른골목이적당하오.)

제1의아해가무섭다고그리오.

제2의아해도무섭다고그리오.

제3의아해도무섭다고그리오.

제4의아해도무섭다고그리오.

제5의아해도무섭다고그리오.

제6의아해도무섭다고그리오.

제7의아해도무섭다고그리오.

제8의아해도무섭다고그리오.

제9의아해도무섭다고그리오.

제10의아해도무섭다고그리오.

제11의아해도무섭다고그리오.

제12의아해도무섭다고그리오.

제13의아해도무섭다고그리오.

A rough translation of only the propositional content would be: “thirteen children rush to the road / (as for the path, a dead end is adequate) / the first child says it is scary / the second child also says it is scary” and so on until the thirteenth child.

What would it mean to translate this stanza into English in a foreignizing way (i.e. literally/faithfully)? Orthographically, the rectangular block created by the lines and the utter lack of spacing communicate a sense of breathlessness and monotony. Lines 3-15 are identical except for the ascending number and the change of case marker from “-가 -ga ‘Nominative’ ” in Line 3 to “-도 -do ‘Nominative + also’ ” in Lines 4-15.

If the foreignizing translator wants to retain this visual effect, she

might translate Lines 3-12 as follows: “Thefirstchildsaysitisscary / Thesecondchildtoosaysitisscary …” Yet with this translation, the

English reader would have to try to read each line by making out

individual words one by one in a linear fashion from left to right, as

though the spaces between words were still in place.

This is not the case for the Korean reader of the original, who would

be able to register the lines without the need for such horizontal

separation of words, because the Hangeul script is written in ‘syllable

blocks’ as opposed to linear words formed by the letters of an

alphabet. The translator might propose capitalizing the initial letter of each word to make it more distinguishable: “TheFirstChildSaysItIsScary…” But she would be straying even further from the original, because capitalization is not part of Hangeul.

Then, as did the translator of As I Lay Dying, she might object that the stanza’s visual form and its lack of spacing are mere matters of orthography, whereas the idea of foreignization pertains only to structural aspects of the language used. Yet the breathless, monotonous effect that the original’s visual form conveys is not entirely independent from its phonology and syntax: because Korean lacks stress, the spaceless structure of the stanza allows for a monotonous and almost robotic reading (out loud) of each line without any variation in the rhythm of speech.

In other words, the original conveys the breathlessness without neglecting an aspect of phonology that would otherwise have been in place. But if the reader of the English translation were to disregard the location of the stress in all of the polysyllabic English words and read all syllables monotonously, she would be deliberately ignoring an aspect of English phonology. This very neglecting of stress would thrust itself upon the attention of the English reader and affect her reception of the poem, whereas the reader of the original senses the breathlessness and monotony without receiving the effect of violating the existing aspects of Korean phonology.

Also, because English does not have a direct equivalent of the case suffix “-도 -do ‘Nominative + also’, ” the translator would have to add another word (such as too or also) to Lines 4-15; then these lines would each have one more syllable than Line 3, even though Lines 3-15 all have the same number of syllables in the Korean original. Therefore, a certain degree of domestication is inevitable in order to produce in English something that resembles the original reasonably enough, even in a decidedly literal translation.

Which do you prefer?

Now, I have made four different translations for this excerpt,

each of which is in some ways paraphrased and in others literal.

Each of us can choose which one works best. For those of us who

don't speak Korean, it might help to wonder which one could

best capture something about the Korean original that would

otherwise have been lost. The gloss box beside this paragraph is

only here for the convenience of anyone who wishes to

understand the grammatical breakdown of the original, so we

don't all have to scrutinize it in detail. Here are my four

translations:

Translation 1:

Thirteen children rush to the road.

(As for the path, a dead end is adequate.)

The first child says it is scary.

The second child also says it is scary.

The third child also says it is scary.

The fourth child also says it is scary.

The fifth child also says it is scary.

The sixth child says it is scary.

The seventh child says it is scary.

The eighth child also says it is scary.

The ninth child says it is scary.

The tenth child says it is scary.

The eleventh child says it is scary.

Translation 2:

ThirteenChildrenRushToTheRoad.

(AsForThePathADeadEndIsAdequate.)

TheFirstChildSaysItIsScary.

TheSecondChildTooSaysItIsScary.

TheThirdChildTooSaysItIsScary.

TheFourthChildTooSaysItIsScary.

TheFifthChildTooSaysItIsScary.

TheSixthChildTooSaysItIsScary.

TheSeventhChildTooSaysItIsScary.

TheEighthChildTooSaysItIsScary.

TheNinthChildTooSaysItIsScary.

TheTenthChildTooSaysItIsScary.

TheEleventhChildTooSaysItIsScary.

Translation 3:

13ofchildrenrushtotheroad.

(asforthepathadeadendisadequate.)

the1stchildsaysitisscary.

the2ndchildtoosaysitisscary.

the3rdchildtoosaysitisscary.

the4thchildtoosaysitisscary.

the5thchildtoosaysitisscary.

the6thchildtoosaysitisscary.

the7thchildtoosaysitisscary.

the8thchildtoosaysitisscary.

the9thchildtoosaysitisscary.

the10thchildtoosaysitisscary.

the11thchildtoosaysitisscary.

Translation 4:

13ofahaerushtotheroad.

(asforthepathadeadendisadequate.)

第一ahaesaysitisscary.

第二ahaetoosaysitisscary.

第三ahaetoosaysitisscary.

第四ahaetoosaysitisscary.

第五ahaetoosaysitisscary.

第六ahaetoosaysitisscary.

第七ahaetoosaysitisscary.

第八ahaetoosaysitisscary.

第九ahaetoosaysitisscary.

第十ahaetoosaysitisscary.

第十一ahaetoosaysitisscary.

There is obviously no right answer, and any of the choices results in a kind of compromise, involving both domestication and foreignization simultaneously. Something always gets lost one way or another, and a decision must be made regardless, ultimately at the translator’s discretion.

Bridge to Cultural Translation

Toji (토지, 1969~1994), a novel sequence of twenty-five volumes written by Park Kyong Ni (박경리, 1926~2008), is considered a landmark achievement of modern South Korean literature. Given its daunting scale, I have not yet managed to read through it, so we won't go into details. But I did want to bring it up because of a Korean article I read that talked about translating an excerpt from one of the volumes of Toji into English.

Here are the original sentence and the translation mentioned in the article:

"아무도 안 태워 주더나?" 한복은 고개를 끄덕였다.

"Didn’t any of them offer you a ride?" Hanbok nodded.

The translation is pretty much as literal as it can get, but strangely, it has almost an opposit meaning. So, somebody asks a man named Hanbok whether anybody gave him a ride, and Hanbok nods his head as a reply. What does this mean to English speakers? When we ask someone the same question in English, and she nods, she probably means that she did get a ride. However, what Hanbok means here is in fact that he did NOT get a ride. The article criticizes this translation by saying that it should have been "Hanbok shook his head".

What changed the meaning here? Some of us might be guessing that nodding means 'no' in Korea, while it means 'yes' in the English-speaking world. But that is not the case, either. In Korea, nodding is always the affirmative, and shaking one's head is always the negative, just like in the U.S. So Hanbok is indeed saying 'yes' to the question. Then what is causing the confusion?

What is going on here is that Hanbok is replying in the affirmative to the negative that is in the question. It is the fact that the question went "Didn't any of them..." as opposed to "Did any of them..." that elicited a different response from Hanbok. His nodding means, "yes, it is true that somebody did NOT give me a ride", because Koreans respond directly to the way the question is phrased. By contrast, in English, nodding would have meant "yes, somebody gave me a ride", whether or not the question was phrased in the negative.

This is a notorious cause of confusion among native Korean and English speakers learning each other's language for the first time. It is difficult to determine whether this difference has to do with language or with culture. Nodding and shaking one's head is now an international pair of gestures, and are not part of the syntax of a language that constructs its sentences. I wanted to use this interesting example as a doorway to the second half of translation that will be discussed in this project: the translation of culture.

Up to this point, most of the things we looked at had to do with textual form, not content. But we saw from the Korean translations of Huckleberry Finn that there also are important cultural issues that need to be addressed. Translation involves both the text and the tale it tells. America's history of slavery and racial violence are concepts nonexistent in modern Korea that also need to be translated. From now, therefore, we will explore the translation of culture.

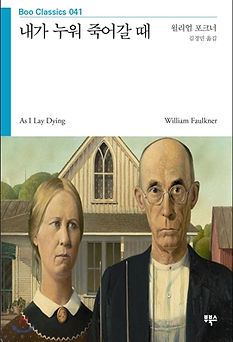

A Korean translation of As I Lay Dying (1930) by William Faulkner (1897~1962).

The cover features American Gothic (1930) by Grant Wood (1891~1942).

They could literally just have said Brazil. literally.

Korean translation of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870) by Jules Verne (1828~1905).

Lee Sang (or Yi Sang) (1910~1937), major Korean poet best known for Ogamdo